What Could be the Outcomes for the Section 232 Aluminum Probe?

Although my colleagues have written in detail exploring the specifics of the Section 232 investigations in steel and aluminum, recently completed by the U.S. Department of Commerce, it is worth considering the likely outcomes.

This is particularly true for aluminum, because the production market is not as integrated as it is for steel. Often, primary producers and downstream are not vertically integrated, making decision-making more complex.

Section 232 buying strategies – download MetalMiner’s Section 232 Investigation Impact Report today!

One can understand why President Trump is taking his time to make a decision on the twin section 232 investigations.

Although the premise of both investigations is the same — namely that steel and aluminum imports threaten to impair the national security of the United States — the two industries and their respective supply chains differ considerably.

A Background of Decline

The U.S. aluminum industry has a primary smelting sector that has been in decline since the turn of the century, but particularly in the last five years, as this graph from Statista illustrates.

Today, the U.S. has just eight plants with a combined annual production capacity of 1.82 million tons. According to Reuters, actual production last year was 785,000 tons, translating into a capacity utilisation rate of 43.2%.

That’s dire by any industry standards and qualifies the Commerce Department’s argument that at such levels an industry cannot be profitable, cannot invest in the future, and cannot afford research, development or innovation.

Yet to get it to the 80% target espoused in the report would require only 669,000 tons of idled capacity to be brought back onstream. We will come back to that shortly, but not before we take a quick look as to where some 90% of U.S. primary aluminium imports are coming from.

Import Sources

As this graph from Reuters shows, Canada, Russia and Brazil are by far the largest suppliers of primary aluminum into the U.S. market. There is no suggestion as to clawing significant chunks of this production back to U.S. shores; 669,000 tons is just the tip of the iceberg.

Sector Snapshot

The major part of the U.S. aluminum industry is made up of downstream suppliers producing semi-finished products, from plate and bar down to sheet, foil, wires, tubular products, and cast and forged parts.

This downstream sector faces a different set of challenges from the primary producers.

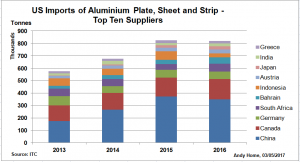

Some semis manufacturers rely on competitively priced imports of primary metal or billets in order for them to compete in export markets or domestically against foreign suppliers for the same finished goods. Other semi-finished manufacturers, arguably more at the commodity end of the market, face intense competition from imported semi-finished products depressing domestic U.S. price levels. The supply base for semi-finished products is different from the primary market, as the below graph from Reuters shows.

Here China, despite previous anti-dumping actions, remains a major supplier and is likely the main target for the Commerce Department’s actions.

Winners and Losers

A blanket tariff increase across the board would clearly create massive winners and losers because of the complexity of the aluminium market.

The Commerce Department is proposing either an across-the-board import tariff of 7.7% or a quota system limiting imports to 86.7% of last year’s levels. A third option would be to target five countries with a draconian 23.6 % tariff, with everyone else subject to a quota also set at last year’s imports. Clearly, in the primary market Canada is going to be given an exemption, so rather than across the board, any tariffs or quotas are more likely to be country specific.

Likewise, with semi-finished products China and its intermediary shipping points, such as Vietnam and Hong Kong, are also likely to be the principal targets. Not surprisingly, the prospect of China being partially shut out of the U.S. market is sending shivers through governments in other parts of the world, fearful of where those redirected trade flows will end up.

Of course, it’s entirely possible nothing will be done.

Blocking Russian and Venezuelan imports of primary aluminum will not immediately make U.S. smelters viable again. Smelter closures have more to do with power costs than solely foreign competition. In addition, as my colleagues Lisa Reisman and Irene Martinez wrote this week, to bring an idled smelter back onstream is a medium-term proposition. A decision in April would not see capacity come back onstream this year, so any action has to be timed carefully.

Want to see an Aluminum Price forecast? Take a free trial!

The LME spiked on the release of the investigation’s findings and CME physical delivery premiums have climbed. For now that’s probably it, but be prepared for further volatility as the decision deadline of April 20 approaches.

Leave a Reply